Judy Middleton (First published 1983 revised 2013)

THE DOME

Brighton is famous for its buildings with a flavour of the exotic East. Work on the Dome was completed in 1808 and it was the first building in Brighton whose exterior reflected an interest in India. However, to be accurate, the Prince of Wales (later the Prince Regent and subsequently King George IV) had already shown an enthusiasm for the East by having the interior of the Royal Pavilion decorated in the Chinese manner. But the success of the Dome must have influenced his decision to re-design the Royal Pavilion with an Indian-style façade rather than a Chinese.

The Dome is an impressive building but it was perhaps a typically English characteristic that it was constructed for the comfort of the royal horses. It was stated, without fear of contradiction, that it was the most magnificent set of stables ever erected in Europe. There were stalls for 41 horses arranged in a circle with an additional 22 stalls in the courtyard. Close attention was paid to ventilation because the glass roof with a diameter of 80 feet could have made conditions inside unbearably hot in summer. As a final touch of equine luxury, there was a centrally placed pool and fountain.

Although the Dome was obviously built to last, its function as an up-market stable was comparatively short-lived. Its next incarnation was to be used as a concert hall and it has fulfilled this function from 1867 to the present day. The building is also home to the much-visited museum and art gallery.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton An Edwardian view of the Dome and gardens |

|

| copyright © J.Middleton View of the Dome and gardens in May 2009 |

THE ROYAL PAVILION

The Royal Pavilion as we see it today was the outcome of the Prince Regent’s desire for an oriental palace and John Nash was the architect chosen for the project. During the first five years of the building programme the Pavilion swallowed up some £148,000. The figure may seem large but it is in fact less than half the final amount spent on the whole scheme; this included the cost of buying the land, erecting the buildings and decorating them. The word unique is often bandied about today but it most certainly describes the Pavilion accurately. People who visit the interior agree that there is nothing like it while the magnificent Banqueting Room and Music Room earn special praise.

However magical we find the Pavilion nowadays, it is interesting to note how quickly it fell out of favour. Queen Victoria found Brighton too crowded and its inhabitants too inquisitive and so she was quite happy to sell off the Pavilion Estate to Brighton Corporation in 1850. Besides, it reminded her of her dissolute uncles and was best left in the past.

Queen Victoria removed the furnishings and other valuable items designed for the Pavilion to her other royal residences. Brighton Corporation was left with empty rooms and did not quite know what to do with them although meetings, balls and assemblies took place there. But it remained something of a white elephant. During the First World War it became a Hospital for Indian soldiers – rather appropriately. Later on there were even thoughts of demolition and the Pavilion remained in this state of limbo for 100 years. Then the work of rehabilitation began and indeed the task of restoration has never ceased since.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton The Royal Pavilion |

|

| copyright © J.Middleton Indian soldiers in the Pavilion's grounds in 1915 |

THE NORTH GATE

It is a rather prosaic name for such a delightful structure. Looking at it on a day of bright sunshine with its warm coloured sandstone and green domes, it is difficult to realise you are standing in an English seaside town.

The North Gate separates the grounds of the Royal Pavilion from Church Street and provides a fitting entrance to the Prince Regent’s exotic palace: except the Prince himself never saw it. However, the Prince of Wales feathers above the entrance are an acknowledged of his inspiration.

The Prince had planned the gate in 1816 but it was not actually built until 1832, by which time William IV sat on the throne. The reason for the delay was not due to a lack of money but to an obstinate Brighton blacksmith whose premises were at 9 Marlborough Place, the site now occupied by the North Gate and North Lodge. The cunning blacksmith obviously thought he was on to a good thing and he refused to sell at a reasonable price. On the contrary he raised the amount of money he required to four times the actual value of the property. Eventually the Town Commissioners, who set great store by the royal patronage, stepped in, purchased the property by compulsory purchase, and presented the site to the King.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton An Edwardian view of the North Gate of the Royal Pavilion |

|

| copyright © J.Middleton The North Gate viewed from the south and north |

THE SOUTH GATE

The South Gate we see today is not the original entrance to the Royal Pavilion; in fact there have been three gateways on the site. The first was demolished in the 1850s and was replaced by two lovely little structures complete with domes and minarets. They were in perfect sympathy with the architecture of the Royal Pavilion.

By contrast, the present South Gate has been criticised as being far too sombre to match the exuberance of the Pavilion. But for purists the South Gate is more authentically Indian in style than the Pavilion, which is a hybrid of different styles. In any case, architectural frivolity would not have been appropriate because the gate was a memorial to Indian soldiers who were nursed, and some of whom, died at the Royal Pavilion when it served as a hospital during the First World War.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton An early Edwardian view of the former South Gate |

Thomas Tyrwhitt was the architect of the South Gate and 16th buildings at Gujerat were his inspiration. The Maharajah of Patiala unveiled the South Gate in October 1921. He was a fitting choice to do the honours because some 28,000 men from his state served in almost every theatre of war.

The Maharajah left a foggy London, travelled down aboard the Pullman car Bessborough, and arrived at the station to find Brighton basking in bright sunshine and a full civic welcome laid on to greet him. A newspaper report described the Maharajah as ‘a sturdy figure of a man, bearded and smiling and wearing exquisite pearl earrings and khaki turban’. In his speech the Maharajah told how many wounded Indian soldiers on returning to their families in northern India could tell the tale of how they had been nursed in a royal palace. He added ‘these memories are a great Imperial asset in these days of restlessness’.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton The "new" replacement South Gate of 1921 |

THE CHAIN PIER

Anybody who knows about Brighton will surely have heard about the Chain Pier. Although we think of it as belonging to old Brighton, it is relevant to try and appreciate the perspective of people who saw it newly built in 1823.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton A Victorian postcard showing the Chain Pier |

The pier rested on timber piles driven almost ten feet into solid rock. The massive cast-iron towers weighed fifteen tons each while in the suspension chains, each link was ten feet in length and weighed 112lbs. The suspension chains were firmly anchored in the cliff.

The architectural style derived from the Middle East and the towers were inspired by pylon gateways of ancient Egypt. It was not because of the general interest in Egypt since Nelson’s great victory at the Battle of the Nile in 1798 but rather for the practical reason that this form was able to bear the great weight required of it.

However, the inspiration for the entrance kiosks derives straight from the Royal Pavilion and were all that remained intact after a violent storm on 4th and 5th December 1896 destroyed the Chain Pier. The kiosks were rescued and placed on the Palace Pier, then in the process of being built.

THE WEST PIER

The next pier to be built at Brighton was the West Pier and on 6th October 1866 it was opened to the public. Eugenius Birch designed the edifice and he was something of a specialist in piers because his final tally came to fourteen.

Apart from the timber used for fender piles and the deck planking, the rest of the structure was made of iron, both cast iron and wrought iron. The glazed screen extending down the length of the pier with seating and a projecting roof was something quite new. The general feeling was that Mr Birch was to be congratulated on providing such a novel feature. It was hoped the pier would prove attractive to ladies because, as the Chairman of the company that built it remarked, ‘where ladies were gathered together the gentlemen would be sure to congregate’.

There were several touches of the ‘seaside Eastern’ about the West Pier including the charming octagonal kiosks with a roof surmounted by a delicate structure resembling a howdah. When the theatre at the end of the pier was added in 1895, the theme was repeated with a domed roof and minarets at the corners. Other Eastern touches were the pierced ironwork of the side seating and the serpentine forms curving around the lamp standards, both echoes from the Royal Pavilion.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton Edwardian view of the West Pier |

|

| copyright © J.Middleton An early Edwardian view of the West Pier |

The West Pier closed in 1975 because it was deemed unsafe. But there were always hopes that eventually money would be found to return it to its former glory – especially since it was granted Grade I listed status in 1982. Unhappily this never happened. While Government departments, Brighton Council, organisations and various people debated the question of funding, stormy weather accelerated the pier’s decline. Starting in 2002 and again in 2004 and 2005, stormy seas and strong winds caused parts to fall into the sea. But the worst disaster was the two fires of 2003, which destroyed everything except some of the ironwork. Yet the old lady seems reluctant to leave and the gaunt ruins of the concert hall remain an iconic structure, marooned out at sea.

THE PALACE PIER

The third pier at Brighton was the Palace Pier and indeed for a brief period all three were in existence at the same time. When compared with the rapidity with which the Chain Pier was erected, the Palace Pier took its time in being built. R. St George Moore was the architect.

Work started in 1891 but it was not properly finished until 1901. However, the grand opening took place on 20th May 1899 when the Mayoress of Brighton presiding over the event. The day turned out to be very blustery and the ladies were worried about their skirts. This was more than matched by the concerns of the men, uneasy about the regulation tall hats they had donned especially for the occasion. The wind also upset the plans of reporters from local newspapers who waited, pencils poised, to take down the words of celebratory speeches but were unable to hear a thing.

The Palace Pier is the most unashamedly Eastern of Brighton’s piers with its profusion of domes (popularly called onions) and its oriental archways. In October 1973 when some ‘onions’ were literally washed overboard because a barge broke loose and hurled itself against the pier, it was felt essential to replace them.

One of the most original features of the pier was the series of iron arches with their delicate scrolls and latticework (again a reminder of the Royal Pavilion). At one time they were outlined with electric lights and made the pier an attractive sight at night. Originally, there were six groups of arches; the feature being continued right up to the entrance. But in 1910 the latter group was replaced by the present clock tower, which had come from the Aquarium. By 1983 there was only one complete set of arches left.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton Edwardian views of the Palace Pier |

|

| copyright © J.Middleton Brighton Pier (Palace Pier) in 2009 |

|

| copyright © J.Middleton The iron arches of the Pier |

|

| copyright © J.Middleton Brighton Pier |

THE MADEIRA LIFT

|

| copyright © J.Middleton An Edwardian view of the lift in Madeira Drive |

|

| copyright © J.Middleton The lift in Madeira Parade in 2009 |

The lift was part of the terrace completed by 1890. It was worked by hydraulic power and a contemporary fan wrote ‘it has perfect action – noiseless and un-vibrating. It ascends like a balloon, or descends without the occupants of the car being conscious of motion’.

Today the lift enjoys the status of a Grade II listed building and in recent years some £250,000 has been expended on a thorough restoration.

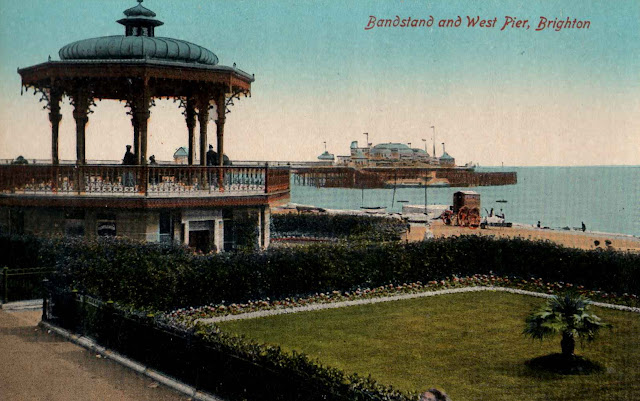

THE BANDSTAND

The bandstand on the seafront dates from 1884 and like Madeira Terrace, it is one of Brighton’s cast-iron triumphs. Although the material is tough, it can be worked to create a tracery with a delicate, lacy effect. The roof is a shallow dome surmounted by a coronet of two smaller domes and it is quite unlike the shape of the usual Brighton domes.

The bandstand was built to provide shelter from sun or rain for the bandsmen – often a military band – while they provided the music that was such an essential part of a stroll along the promenade in more elegant days.

But like all iron structures in sea air, the bandstand needed a considerable amount of maintenance. By the early 1980s it had fallen into such a state of disrepair that the catwalk linking it to the promenade was removed for safety reasons. But in July 2009 the newly refurbished bandstand was unveiled to universal approval. The work cost the enormous amount of £950,000 but that included a new copper roof. The castings needed to be grit-blasted to remove rust and no fewer than 40 coats of paint. And the band played on for the first time in 35 years.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton Edwardian view of the Bandstand with the West Pier in the background |

|

| copyright © J.Middleton The Bandstand in 2009 |

WHAT IS IT?

This unusual looking building stands on the corner of Paston Place and St George’s Road. The dome looks somewhat incongruous because there is nothing of a similar style nearby. If it was built to attract attention, it certainly succeeds.

It was the brainchild of Sir Albert Sassoon who lived not far away at 1 Eastern Terrace. Whilst living there, he entertained the Prince and Princess of Wales in 1881 and the Shah of Persia eight years later. Fittingly with such an address and with such a mausoleum, Sir Albert did have connections with the East. When he died in 1896 it was stated he was ‘one of the richest merchant princes of India, and one, moreover, who made a most philanthropist and public use of his wealth’.

Even in those days it was unusual to have a private burial place in the middle of a built-up area and things had to be done in accordance with Home Office requirements. The second person to be buried there was Sir Albert’s son, Sir Edward Sassoon, who died in 1912. The third baronet, Sir Philip Sassoon, was only 23 years old when his father died and it seems he did not want to remain in Brighton. In the 1930s he sold the house in Eastern Terrace and the mausoleum; the coffins were removed and re-buried in London.

THE WESTERN PAVILION

|

| copyright © J.Middleton The Western Pavilion |

Amon Henry Wilds designed the house in around 1830. It is a surprising architectural essay from such a family because his father Amon Wilds in partnership with Charles Augustin Busby designed Kemp Town, Brighton while Busby on his own designed Brunswick Town, Hove. Their signature style was the one known as Regency – that is stuccoed houses with curved frontages and ironwork balconies. Perhaps the Western Pavilion was AH Wilds’ excursion into something completely different. If a Prince could dream of Xanadu, why should not a local architect indulge in an Eastern fantasy as well? After all, it was his own house and not for a client. It must have been great fun working out how to furnish his oval-shaped rooms while the exterior served as a mute but potent advertisement for his skills.

Today the building is a private home once more, having been used as an office or an annexe in intervening years.

THE CHATTRI

The Chattri is located on the Downs above Patcham at some 500 feet above sea level. Its whiteness is emphasised by its green surroundings and it is because of this definition that the Chattri creates the illusion it is closer than it really is – as many a casual walker setting out from Patcham has discovered.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton The Chattri |

EC Henriques, the Indian architect, designed the edifice and it was built of white marble; the cost being shared between the India Office and Brighton Corporation. The Chattri marks the spot where Sikhs and Hindus who were nursed at the Royal Pavilion Military Hospital during the First World War, and died there, were cremated. As far as possible the ritual of the burning ghat was observed with the symbolic use of metals, grain, flowers and scent. After cremation, the ashes were scattered at sea. The Muslims had different funeral rites and were buried with full military honours at a cemetery near the Shah Jehan Mosque at Woking, Surrey; But the inscription at the Chattri stresses it is a memorial to all Indian soldiers.

The Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII, afterwards Duke of Windsor) unveiled the Chattri in February 1921. Even he had to walk half a mile to get there. The civic authorities did their best by binding the wheels of the official car with ropes to enable it to get a grip on the rather greasy ground. Fortunately for all concerned, the sun shone and the Prince managed to reach the Chattri without slipping over.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton The Prince of Wales unveiling the Chattri in 1921 |

Copyright © J.Middleton 2013page layout by D.Sharp