Judy Middleton 2002 (revised 2023)

|

copyright © J.Middleton

From left to right these buildings are Warnham

Court, Victoria Court, and 15 Grand Avenue. |

Background

Grand Avenue was designed as the central space of

the ambitious development proposed by the West Brighton Estate

Company with First and Second Avenues to the east and Third and

Fourth Avenues to the west. Grand Avenue was built on land formerly

part of the Stanford Estate that stretched from Preston Manor to the

coast road at Hove (for additional information, see under First

Avenue.) The seafront lawns formed part of the scheme, and were

intended for the use of estate residents.

|

copyright ©

Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

The broad width of Grand Avenue can be

appreciated in this c1917 postcard |

Grand Avenue is the broadest street in Hove,

measuring 70 ft from kerb to kerb. The land had no building line from

previous housing on the site and so the company could afford to be

generous with the allocation of space. The broadness also points to

confidence in their ambitious scheme but it seems the developers

might have missed the boat with regard to Grand Avenue. There have

always been fluctuations in the strategy of house-building and Grand

Avenue, despite its upmarket name, hit a downward curve. In May 1900

the company was obliged to admit ‘Grand Avenue has not proved to be

a business success owing to the absence of demand for high-class

residences.’

|

copyright © J.Middleton

A nostalgic view of

the original houses on the west side, now long gone. |

Development

Building work at Grand Avenue was sporadic,

starting off in 1877 when the Hove Commissioners gave planning

approval for the designs of James Ockenden, junior, for three houses,

then there was a pause until 1892 when the well-known builder John

Thomas Chappell proposed erecting a house on the west side, while in

1900 Hove Council gave approval to plans drawn up by A.F. Faulkner on

behalf of W. William Willett. Today, a house built under the auspices

of William Willett is a guarantee of a well-built residence and

indeed a Willett-built house is an accolade.

|

copyright © J.Middleton

This impressive statue of Queen Victoria

designed by Thomas Brock was unveiled in 1901 |

As a result of this drawn-out time-line, there was

no overall design, as had been the case with

First and

Second Avenues. Some houses in Grand Avenue were built using white/yellow

brick popular in other parts of the estate, while others were built

in red brick.

Another indication of slow progress was the time

it took before the entire road was classed as a public highway. In

1894 one part was declared a public highway, another stretch of road

followed in 1899 with the last parts completed in 1902 and 1903.

Up until 1893 the company intended to make a

private road on the west side but in February of that year, they

abandoned the plan. Hove Commissioners gave permission for houses to

be built, provided they kept to a building line compatible with the

east face of 1 King’s Gardens, and the east face of the south wing

of Grand Avenue Mansions. By 1899 only one house had been erected on

the west side.

Eventually, Grand Avenue did begin to live up to

its title, and there were several substantial residences with equally

grand residents. No doubt the ambience was enhanced by the erection

in 1901 of the magnificent bronze

statue of Queen Victoria at the

south end. This statue was intended to celebrate Queen Victoria’s

Diamond Jubilee but by the time it was ready, Queen Victoria had died

at Osborne House. The unveiling of the statue was necessarily a

somewhat muted affair in order to respect the memory of the late

sovereign.

Some of the houses in Grand Avenue could boast of

a third tap in their bath-tub so residents might enjoy a sea-water

bath in the privacy of their own home. To provide this amenity, there

were tanks under the lawns opposite Grand Avenue capable of holding

29,000 gallons of sea-water, which was drawn from the sea at high

tide. The Easton & Anderson pump was installed in its underground

chamber in 1872 and it did not cease pumping until 1940 when the last

man to supervise the pump was Mr C.S. Goodwin. It is said that the

equipment remains in situ.

The large block of flats on the east side of Grand

Avenue was erected in 1939 and it was considered one of the best

mansion blocks in town with spacious rooms. For instance, a lounge in

a first-floor flat measured more than 19 feet by 12 feet and in

October 1990 this flat was up for sale at £175,000.

Grand Avenue War Memorial

|

copyright ©

Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

The War Memorial was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944),

the bronze statue of St George was designed by

Sir George Frampton (1860-1928) |

At the north end of Grand Avenue there is the War

Memorial with the bronze figure of St George on top of his pedestal.

It is quite a contrast to the massive bulk of Queen Victoria at the

south end of Grand Avenue and St George looks surprisingly small and

fragile. Indeed, the figure has led to confusion as to its sex

because in a recent magazine article it was boldly stated the figure

was St Joan of Arc. Quite what St Joan of Arc had to to do with Hove

was not explained.

|

Image from the Academy

Architecture & Architectural Design (1904)

This statue of St George is on a Boer War (1899-1902)

Memorial in Radley College, Oxfordshire and was also

designed by Sir George Frampton R.A.

Sir George based his 1920 design of Hove's

St George statue on this earlier Radley College creation,

albeit without the halo and dragon.

|

Now that it is no longer politically correct to

celebrate St George’s Day, as used to happen at Hove, young people

have perhaps lost sight of the fact that St George is the patron

saint of England. It is somewhat annoying that it is perfectly fine

to celebrate St Patrick for Ireland, St Andrew for Scotland and St

David for Wales, but definitely not St George for England.

The war memorial was designed by the celebrated

Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944). The great man could not be present in

person when the Hove War Memorial was unveiled because he was busy in

India with the palatial government buildings in New Delhi, still

regarded as a masterpiece.

The

column and plinth of the war memorial are of granite and the whole

edifice cost £1,537. Hove lost a large number of its young men in

the First World War and there was simply not enough space to remember

each of them by name at this site and people had to be content with

the inscription

Their Name Liveth for Evermore,

a text from the Bible chosen by Rudyard Kipling and much used in war

cemeteries in this country and abroad. On the north side there is the

following inscription In

ever Glorious Memory of Hove Citizens who gave their lives for their

country

in the Great War and World War.

Instead, the names of over 600 men lost in the

First World War are recorded on brass wall plaques in the vestibule

of Hove Library. In the end this was not a bad idea because it meant

that names, which had been omitted by mistake, could be added without

too much trouble. Also in such a public place there is no chance of

vandalism, and the staff ensure that the brass remains highly

polished, as befits our heroes.

|

copyright © J.Middleton

Hove War Memorial Dedicated 27 February 1921 (Floral Tributes)

|

The Hove War Memorial was unveiled on 27 February

1921 by Lord Leconfield in front of a vast crowd. The photographers

were out in force, and many postcards of the scene were produced.

|

copyright ©

Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Armistice Day celebrations in Grand Avenue, 13 November, 1937

|

Second World War

On 4 September 1940 five high-explosive bombs and

one unexploded bomb fell on Grand Avenue, Salisbury Road and the

Sussex County Cricket Ground. Nobody was killed at the time, but ten

days later three soldiers were killed when the UXB exploded.

In 1940 and 1941 Mr J. Ellman Brown of Shoreham,

on behalf of the Admiralty, requisitioned properties in Grand Avenue.

Some of them, plus the Princes Hotel, became the wartime

establishment of

HMS Lizard, a combined operations holding and

operational base.

|

copyright ©

Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

1914 advert for the Princes Hotel from the Brighton Season Magazine |

This part of Hove became virtually a no-go area for

residents and indeed the rolls of barbed wire, guarded by military

personnel, blocked off the junction with Church Road. The seafront

became a restricted area with the beaches mined and gun emplacements

on the promenade. No maintenance work on beach or groynes could be

carried for the duration and by the time peace was declared, Hove’s

seafront was a pretty miserable sight.

In November 1945, nearly all the requisitioned

buildings were restored to their owners, with compensation being paid

eventually.

House Notes

Number 1 – Sir George Donaldson

(1848-1925) occupied this house from around 1916 until his death. He

was born on 25 May 1848 of Scottish parentage and it was remarked

that he received a much better education ‘than used to fall to the

lot of art dealers in England’. He travelled a great deal in

northern Europe and built up a solid knowledge of art history. By the

1890s every connoisseur knew his gallery in New Bond Street, London.

He once sold a large Velasquez for £30,000.

Donaldson was also a great lover of music, his

favourite instrument being the violin. He amassed musical instruments

with historical associations for a period of thirty years and in 1894

presented the entire collection to the Royal College of Music, and it

became known as the Donaldson Museum. His treasures included the

following:

An upright spinet made in northern Italy in the

15th century – said to be the oldest keyboard instrument

in existence.

A clavicembalo (dated 1531)

A pair of ivory and ebony mandolins (belonging to

the last Doge of Venice)

A tortoiseshell guitar (played by David Rizzio

before Mary, Queen of Scots)

A guitar (once belonging to Louis XV when he was

Dauphin)

A chitarrone (the property of Titian, and latterly

belonging to Rossini)

The collection also included manuscripts by Mozart

and Rousseau, and Handel’s gold-enamelled portrait ring.

Donaldson was a Fellow of the Royal College of

Music, and a director of the Royal Academy of Music to which he made

a large loan for the construction of a new building in Marylebone

Road.

In 1900 Donaldson presented a collection of

furniture to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Donaldson was once heard to say that Brighton and

Hove had no equal in Europe, and as a mark of respect in 1917 he

donated a beautiful copy of Canova’s Dancing Girl and it was

installed in the entrance hall of

Hove Town Hall.

In 1872 he married Alice, daughter of John

Stronach of Edinburgh, and there were three sons and four daughters

of the marriage.

Donaldson had another property at 2 Eastern

Terrace, Brighton, and it seems that he used the Grand Avenue house

as his personal museum, indeed the 1919 Directory identified the

house as Sir George Donaldson’s Museum, caretaker Alfred Sharpe. By

1921 his sole address was at Grand Avenue. The interior was glimpsed

in the Brighton Herald (22 December 1917) when Donaldson threw

the house open to the public for an entrance fee of 2/6d, all

proceeds going to the Red Cross. The reporter thought the house had

‘perhaps the most wonderful collection pf beautiful and historic

furniture’ in the country. He enthused about the English Room where

Donaldson could:

‘tell you how the dark oaken floor came from an

ancient building, the linen panel walls from another, the great

carved rafters from another; how the magnificent Elizabethan

fire-place, richly wrought with cunning carving, with a fireplace

where a sheep might be roasted whole, came from a certain ancient

hostelry. The gorgeous gilded chandelier, hanging like an eternal

sunshine against the rich darkness of old oak, can remember the days

when Englishmen fought Englishmen in the War of the Roses. Above the

oak panelling which surrounds the room is a seven-ft frieze of

Jacobean needlework where hundreds of quaint figures and animals

sport amid a tangle of floral decoration. On the walls are pictures

of haughty ladies, very stiff with their gold brocade collars […]

The great oriel-like window with its panelling of stained glass is

quite in the Elizabethan tradition.’

There were displays too of letters and documents

bearing the handwriting of Mary, Queen of Scots, Elizabeth I, James

I, Charles I, William IV, Queen Anne, Oliver Cromwell, Dr Johnson,

David Garrick and Horatio Nelson. Queen Elizabeth’s letter ended

with ‘scribbled with my own racked hand Elizabeth R’.

Another room was devoted to the female art of

needlework, with examples of 16th, 17th, and

18th centuries.

Donaldson died at 1 Grand Avenue in the early

hours of 19 March 1925, having been in failing health for some time,

and his widow died in 1929.

In 1926 Hove Council gave planning approval to

W.H. Overton on behalf of Mr J. Worton to convert the property into

flats.

Number 2 – The house was built by James

Ockenden in 1877. In 1893 Mr and Mrs Raphael lived here. On 1 May

1893, their youngest son married

Flora Sassoon, daughter of Mr and

Mrs Reuben Sassoon, who were friends of the Prince of Wales. This

grand society wedding was conducted in a London synagogue, and the

Prince of Wales and the Duke of Cambridge attended the reception

afterwards. The Raphael’s London address was 31 Portland Place.

Another notable occupant of the house was Jeremiah

Colman (1853-1939) whose father was Edward Colman, one of the

original founders of the famous firm J. & J. Colman, mustard

manufacturers of Norwich. Jeremiah Colman first came to know Hove

when he attended Mr Wyatt’s school in Victoria Terrace. He became a

London merchant, and in later life was chairman of several companies

in the City of London. Jeremiah Colman was elected Mayor of Hove in

1899 and served for three years; it was Mrs Colman who unveiled the

statue of Queen Victoria at the foot of Grand Avenue. Colman’s

mayoralty was by all accounts ‘one of the most brilliant that Hove

had known’.

This house was the couple’s last move –

previously they had lived at Wick Hall (the original house rather

then the flats) while in the 1890s they lived in King’s Gardens.

According to Violet Raby, who was once head parlour maid at the Grand

Avenue house, the Colmans kept a large establishment of fourteen

servants. When Violet left service to be married, the Colmans

presented her with a canteen of cutlery as a wedding present. In 1986

Charles and Violet Ravy celebrated their golden wedding anniversary.

|

copyright © D. Sharp

Lt Col. L. M. Colman in his younger days

|

Like the ‘mustard’ Colmans, who were famous

for their benevolence, Jeremiah Colman also helped many deserving

causes, particularly during the First World War. During this time he

raised £1,335 towards the Indian Famine Fund, and the Lord Mayor

congratulated him particularly because it was the first contribution

from the provinces of more then £1,000. But as the

Sussex Daily

News (July 1939) noted ‘He was a man who was fond of doing good

work by stealth, and his benefactions in this respect will probably

never be known’.

The Colmans celebrated their golden wedding

anniversary in 1932 and Mrs Colman died on 2 May 1935 aged 74 – her

tombstone inscription reads ‘beloved wife and companion for 53

years’ – the couple had two sons and a daughter. Jeremiah died in

July 1939 and his funeral service was held at

All Saints – it was a

fitting place for the ceremony because he had been treasurer of the

building fund for some years.

During the Second World War, Mr D.M. Colman,

Lieutenant L.M. Colman, and Mrs Hunt lent this house for the

duration, and it served as a Red Cross depot from 1940 to 1945.

By November 1994, the house, long since converted

into flats, was called Grand Court Mansions, and a second-floor flat

was on sale for £79,500 – it had two bedrooms and a lounge

measuring 24 feet. There was a resident caretaker, and a

wood-panelled lift served all floors.

Number 4

|

copyright © J.Middleton

Number 4 Grand Avenue can be seen on the east

side |

|

copyright © J.Middleton

In this photograph the large block of flats on

the left was built in 1939 on the site once occupied by number 4 |

The West Brighton Estate let

this house for the war effort and from 6 April 1915 to March 1919 the

building served a useful purpose as the Hove War Hospital Supply

Depot. During this time some 3,000 voluntary workers, nearly all of

them women, toiled away making items such as bandages, dressings,

swabs, and splints, and despatching drugs, food and clothes to

British prisoners of war abroad.

|

copyright ©

Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Advert from the Brighton & Hove & South Sussex Graphic |

|

copyright ©

Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

The manufacturing of bandages at the Hove War Hospital Supply Depot in 1915 |

Moreover, the workers paid sixpence

a week for the privilege of working there. This money was used for

administration costs, which meant that all donations could be used to

purchase raw materials. The depot also took over Airlie House

opposite. The total output was impressive:

|

copyright © J.Middleton

George Robey’s widow lived in this building.

This postcard dating from 1906

depicts her husband and two children |

Roller bandages

780,974

Sewn bandages

154,780

Splints, metal / wood

13,164

Crutches, bed-cradles, bed rests, tables

6,353

Dressings & appliances

884,026

Ward linen, etc

80,413

Articles of clothing, etc

Slippers & ‘trench feet’

16,629

Socks, mufflers, mittens, etc

37,221

Miscellaneous

31, 062

The grand total came to 2,106,676 – a

magnificent achievement.

In 1939 a large block containing 55 flats was

built on the site of the original house and grounds. In 1939 Sir

Henry Wood, the first conductor of the Promenade Concerts, stayed at

the

Old Ship Hotel, Brighton, before renting a flat here. He

used to travel up and down to London on the train, but he was such a

well-known figure that he found people wanted to talk to him when all

he wanted was to be able to get on with his work. Later, he moved to

Hertfordshire, and he died in 1944 at Hitchen.

Frank Henry Nixon lived at flat number 4. He was Mayor of Hove from

1958 to 1960, having joined Hove Council in 1953, and in 1966 he was

elected an Alderman. He was strongly opposed to the idea of Brighton

and Hove being amalgamated, but he was in favour of high-rise flats

being erected at Hove because it provided more homes in less space.

Nixon was a senior partner in a London firm of Lloyd’s brokers, and

he was a Freeman of the City of London.

Lady Robey lived at flat number 9 from 1958 to the

1980s. She was the widow of Sir George Robey (1868-1954), the famous

entertainer, popularly called the Prime Minister of Mirth. Lady Robey

was obliged to move out of her flat when she broke a leg. She died in

June 1981 aged 83 and she left £137,000 net.

Number 6 – This house was built in around

1880 to the design produced by E.J. Ockenden in yellow stock bricks –

it became a listed building on 2 November 1992.

Numbers 8, 9, 10, 11

|

copyright © J.Middleton

These houses earned listed building status in

1992 |

By contrast to

number 6, these houses were built of red brick in what has been

labelled the Surrey vernacular style. A.F. Faulkner was the architect

and William Willett was the builder. The gable ends of number 9 have

been rebuilt, possibly because of wartime bomb damage. These houses

became listed buildings on 2 November 1992 – a bit like bolting the

stable door after the horse has bolted because so many of the

original houses have been demolished to make way for blocks of flats.

Number 11 – In the 1890s the idea of

founding a public library in Hove arose, but first of all the Hove

Commissioners wanted to know the public’s opinion on the matter.

Voting papers were issued on 28 March 1891 and collected two days

later. The result was that 1,197 people voted in favour of a library,

502 voted against it, 499 did not reply, and there were 167 spoiled

papers.

William Willett offered to rent rooms at 11 Grand

Avenue for the purpose. There was some haggling over money but Mr

Willett firmly stated the lowest terms he was prepared to offer were

£100 a year for the first two years, and £150 a year thereafter, on

a seven-year lease.

|

copyright © J.Middleton

Number 11, the original location of Hove Library |

Hove Commissioners had £500 set aside for

library purposes, which had to last six months, and it was clearly

not enough. Thus it was decided to open a reading room for the first

six months, and found a reference library to which the commissioners

hoped there would be many donations.

The wealthy people of Hove rose

to the occasion, including Mr Howlett who donated volumes of Punch

(1840-1890) strongly bound in green calf, while Mr Metcalf,

Hove’s Medical Officer of Health, undertook to provide dictionaries

in English, French, German, Latin and Greek. The newsroom opened on

14 December 1891 and the hours were from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m. People

could peruse ten daily newspapers, 20 weekly papers, and 30 monthly

magazines. Ever keen to save money,

Hove Commissioners decided there

was no need to employ a librarian – a caretaker would do. This

decision was quickly reversed and Mr J.W. Lister became Hove’s

first Chief Librarian at a salary of £70 a year. He produced a list

of around 4,000 books that should be purchased to stock the lending

library, which opened in October 1892. It is interesting to note that

members of

Hove Library in 1893 included the following:

219 gentlemen

1 stockbroker

199 students

139 domestic servants

3 blacksmiths

1 corset-maker

1 livery stable keeper

The lease on the building expired on 24 June 1898,

and it was renewed for a further three years. By this time the floors

were beginning to buckle under the weight of books and people, and it

was decided the library must find premises elsewhere. On 23 June 1901

Hove Library moved to

22 Third Avenue, and eventually in 1908 to a

purpose-built edifice in Church Road.

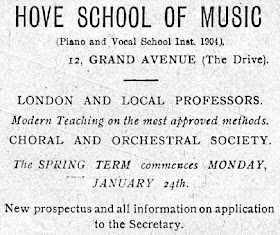

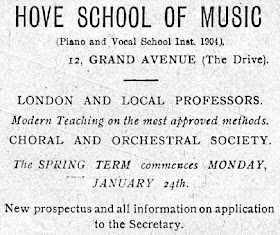

Number 12

|

copyright ©

Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Advert from the 1916 Brighton & Hove & South Sussex Graphic |

In the 1930s a Miss I.

Rowntree ran a boys’ prep school on the premises. The 1951

Directory noted that William Willett Ltd occupied the house, while

next door the First Church of Christ Scientist was to be found.

By the 1980s the London & Manchester Insurance

Company owned the building – most of it was occupied by Whtehead’s,

estate agents, with the architectural firm of Morgan Carn &

Partners located in the upper portion. In 1984 a private investor

paid just over £260,000 for the house.

Number 15 – The house was built in 1939

for Dr (Edmund) Distin Maddick (1857-1939), a Quaker, a Surgeon

Commander in the Royal Navy, and a film pioneer, with an interest in

architecture. He was an extraordinary man with a distinctive name. He

was also very well connected because besides being on social terms

with the king of Italy, he was also in the society milieu of Edward

VII and George V, and once accompanied the Prince of Wales (later the

Duke of Windsor) on his world trip.

According to his son, Major Strafford

Byng-Maddick, Dr Maddick was Army Director of Kinematography during

the First World War and no doubt was involved in the making of the

unique film of the Battle of the Somme made on the first day of

battle, 1st July 1916; this film was shown before an

invited audience at the Scala, Charlotte Street, London on 10

August 1916, which Dr Maddick owned. This irreplaceable film ended up

in a safe in his son’s house, and the major moved to Albany Villas,

Hove in 1927. The film was ‘lost’ for some years but fortunately

surfaced eventually. In 2005 the film was afforded the accolade of

being of world significance.

The house in Grand Avenue was built of red brick

with white marble floors, while the exterior resembled the bridge of

a ship. Dr Maddick caused a flagpole to be erected on top of which a

carved, golden hand pointed skywards. It is said that he hoped to

build a cinema in Hove too.

Dr Maddick was buried in an extraordinary

mausoleum in West Norwood Cemetery, now a listed building. The

interior was lined with mosaic and marble, while the exterior was of

Portland stone. It is instructive that, in a similar way to his

golden hand at Hove, the pinnacle of the unusual mausoleum roof is

topped by the figure of Christ placing a blessing on the head of a

child. Dr Maddick’s tomb has his initials D.M., which he must have

been aware stood also for Dis Manibus (to the souls of the departed)

known to any student of ancient Roman tombs.

In the 1940s Mr and Mrs Freedman (of the Dorothy

Norman shop chain) moved into this house, which was called Fyfteen,

and stayed until it became the last privately owned house in Grand

Avenue. Norman Freedman was born to poor, Jewish parents within

earshot of Bow Bells and thus he was a cockney, while Dorothy was

born in Chingford.

Dorothy and her mother moved to Hove in 1932 and

Norman soon followed. They opened their first Dorothy Norman shop in

Imperial Arcade, Brighton, with the assistance of an overdraft of

£100 from Barclay’s Bank. The shop was run on such a shoestring

that shelves were packed with empty boxes to give the impression of a

well-stocked interior. They sold real leather handbags for 3/11d

or 4/11d. Business built up steadily and the couple were

able to marry in 1934 at Middle Street Synagogue.

During their 30 years in business they opened

branches in Worthing, Eastbourne and Tunbridge Wells. Meanwhile,

their Brighton shop moved three times – they moved from Imperial

Arcade to Western Road, and when the premises had to be demolished to

make way for Churchill Square, they moved further west along Western

Road in 1969. Norman Freedman was founder and senior trustee of the

Jewish Home for the Aged in Brighton, and a life governor of the

Norwood Orphanage for Jewish children.

In 1949 Dorothy became ill with multiple

sclerosis, but she continued to play an active part in the business.

Norman was elected to Hove Council in 1960 and he was Mayor of Hove

from 1969 to 1970 – he was the second Jewish Mayor of Hove, the

first being Alderman Barnett Marks. Norman stated that he would use

his own Rolls Royce on official occasions, and nursing sister Mrs

E.M. Wallace would accompany the Mayoress in her wheelchair

everywhere.

Norman loved to cultivate the garden of his house

in Grand Avenue – there were two palm trees, while grapes grew in

the octagonal greenhouse on top of which was Dr Distin Maddick’s

gold hand, safely preserved when the flagpole was removed. Inside the

house, the walls of the magnificent drawing room were hung with peach

silk. A fine, wrought iron balustrade was added to the staircase, and

over the stairwell the words ‘Love, Life, Labour and Light’ were

embossed on the ceiling.

Dorothy Freedman died 1 February 1973 and her

funeral service was held in the Jewish section of Hove Cemetery –

gentlemen were reminded that they must wear head coverings. Norman

closed down his business operations and retired. But later he married

Mai, widow of another Hove councillor. In 1979 Norman sold the house

for a quarter of a million pounds and moved into a neighbouring

penthouse worth £100,000. The house was demolished and a block of 33

luxury flats was built on the site. Norman Freedman died on 15 June

1984 aged 77. In May 1985 a seat dedicated to his memory was placed

outside the site of his former home.

Number 20 – The Sussex Branch of the

Royal Amateur Art Society held an exhibition in this house from

around 1904 to 1906, courtesy of Sir William Chance. There was a

department for painting under the Hon. Mrs Villiers and Mrs

Mavrogodarto, a department for arts and crafts under the Hon. Frances

(later Viscountess) Wolseley, a department for black and white works

under Mrs A.O. Jennings, and a department for photography under Mr

Job. Miss Campion of Danny, Hassocks, was the honorary secretary.

Grand Avenue Lawn

|

copyright ©

Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Early 1900s view of the Grand Avenue lawns, which today is a tarmac car-park !

|

Grand Avenue Lawn ceased to be for the private use

of tenants in 1948 when Hove Council took over control, along with

the former private enclosures of

Brunswick Square, Adelaide Crescent,

Palmeira Lawn, Medina Lawn, and the seafront lawns.

Flats

|

copyright © J.Middleton

Some of the original pillars have been

preserved |

Coombe Lea – This was the first and

largest block of flats built on the west side. containing 84 flats.

It was thus named after the house that once occupied the site, and

where David Duff lived in the 1930s.

In

2021 there was an outcry when the residents discovered plans were

afoot to instal equipment on the top of the building. It was no

trifling matter because there were several devices and three

companies involved. There was 5G who wanted to instal six phone masts

that would be 20-ft high, and a spokesman asserted they would not be

visible from street level whereas the residents strongly disagreed.

Then there were the companies EE and Three who hoped to place three

dishes and eight equipment cabinets on the roof. Campaigners stood

outside with long banners to advertise their opposition before the

crucial meeting of the planning committee. The council also received

no less than 161 objections to the plans. Grand Avenue is part of The

Avenues Conservation Area, which has to be taken into consideration

too. Fortunately, the councillors passed a unanimous vote to turn

down the plans. It does seem a trifle odd that the companies did not

seek the views of the residents beforehand, and indeed Councillor

Gary Wilkinson said he had never before come across an application to

instal phone masts without first asking permission of the freeholder

and the residents. The phone companies stated that because of

lock-down and the increased amount of people working from home, such

installations were necessary. But Phil Balding, a director of Coombe

Lea Grand Avenue Ltd said they already had mobile phone coverage in

the area. (Argus

4/5/21

/ 8/5/21)

However, the matter was not allowed to rest, and it was in 2022 that

Waldron Telecom appealed against the decision. The residents must

have been heartily sick of the on-going drama because the final

decision was not pronounced until July 2023.

It

is interesting to note that Jane Smith, planning inspector, made two

site visits – one in April 2023, and finally in June. She made the

interesting comment that the huge scale of the building naturally

drew the eye upwards, and so of course the masts would have been

highly invisible. The Waldron contention was that the public interest

outweighed the visibility of the masts. But Ms Smith was unconvinced

by this argument and said the preservation of The Avenues

Conservation Area should be the prime consideration. Therefore, she

proposed that the appeal should be dismissed. (Argus

22/7/23)

Ashley Court – This was the next block to

be built and it contained 67 flats.

Warnham Court – This block contains 34

flats.

Victoria Court – This block contains 30

flats.

Number 15 – This block of 33 flats

replaced the last private house in Grand Avenue and its grounds.

Grand Avenue Mansions

|

copyright © J.Middleton

Grand Avenue Mansions – what a pity modern

blocks of flats are nowhere near as elegant as this Victorian

structure. |

Grand Avenue Mansions were the first purpose-built

flats at Hove and the only one erected on the West Brighton Estate.

The plans were dated 17 January 1883, and three days later were

stamped as complying with local byelaws. The architect of Grand

Avenue Mansions was J.T. Chappell of 149 Lupus Street, Pimlico, who

was also responsible for building at least 120 units of the 169 units

on the West Brighton Estate.

The flats were spacious indeed – there being

only two flats on each of the five floors, bringing the total to ten.

Each flat had from three to five bedrooms, and two or three reception

rooms. The building was constructed of yellow brick, sometimes known

as white brick, and there was wrought iron work and a cupola over the

south elevation. The basement was used for stabling horses, and it

was separated from the ground floor by fireproof and soundproof

arching. In 1883 the average rental was £230 a year.

|

copyright ©

Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

The Drawing Room of an apartment in Grand Avenue Mansions. This

c1900 photograph shows a room decorated in an Edwardian style with heavy

curtains and a small harmonium against one wall. A decorative

fireplace with a heavy over mantle and mirror a loudly patterned

carpet and upholstered chairs

|

It seems probable, in view of the blank wall on

the south side, that the structure was the first part of an intended

series of flats stretching down Grand Avenue. But when Grand Avenue

Mansions were built, it was a time of stagnation, and they were not

snapped up as eagerly as it had been hoped. A hall porter was

employed, and his wife helped him in his duties.

A feature of the flats was the three taps on the

bath – the extra one being for sea-water. Until recent years, the

basement still contained the pump that brought the sea-water from the

underground storage tanks beneath the lawns at the foot of Grand

Avenue.

On the south side, Cl;ayton & Black designed

the iron and glass shelter porch, which Hove Council approved on 5

December 1901.

|

copyright © J.Middleton

This lovely iron and glass shelter porch was

designed by Clayton & Black

– it calls to mind a similar

structure outside the old Hove Town Hall –

unhappily it is no

longer there |

During 1981 and 1982 Barratt Southern Properties

Ltd converted the ten flats into 25 units but some were still more

spacious than the norm today. There were also vestiges of former

splendour because when renovation work was undertaken, marble

fireplaces and magnificent cornices came to light and were retained.

The new units ranged from a one-bedroom flat to a three-bedroom flat.

Some had dressing rooms, and several had two bathrooms. The four show

apartments were open for inspection seven days a week.

In August 1982

a one-bedroom flat was advertised for sale at £35,950, with a

two-bedroom flat costing £64,950, and a three-bed flat at £89,950.

The opportunity was also taken to thoroughly clean the exterior

brickwork, which had become dingy after years of pollution from coal

fires. It was a pleasure to be able to appreciate the original brick

colour once more.

Some Grand Avenue Mansions Residents

Kathleen, Lady Harmsworth - She lived at

Flat 3 from around 1934 to 1968. She was the widow of Sir Hildebrand

Aubrey Harmsworth (1872-1929). He was one of five brothers who became

distinguished newspaper magnates and politicians, including Lord

Northcliffe and Lord Rothermere, but Sir Hildebrand was regarded as

the most eccentric of them all. In 1900 he married Kathleen Mary

Berton from New Brunswick and the couple went on to have four sons.

Sir Hildebrand died in April 1929 and the Rector of Hangleton and

Bishop Russell Wakefield conducted his funeral; he was buried on the

south side of St Helen’s Churchyard. Before moving to Grand Avenue

Mansions, Lady Harmsworth had occupied the whole house at 3 Adelaide

Crescent.

Sir (Edward) Milner Holland CBE QC (1902-1969)

– He lived in Grand Avenue mansions during the 1960s. He was called

to the Bar in 1927. Hr rose to the rank of brigadier during service

in the British Army in the Second World War. He was knighted in 1959,

and in 1965 was awarded the KCVO, a personal order in the gift of the

Queen. He was the author of The Holland Report a study of

housing conditions in central London.

Captain J. Glynne Richard Homfray – He

live at Flat 8 from around 1902 to 1934. He was one of the first Hove

residents to become a car owner – some say he was the first. His

vehicle was a French Panhard and he employed a French chauffeur

called Barthelemy who was resplendent in a black, leather uniform.

Captain Homfray was also a keen racehorse owner.

In February 1914, 43-year old Augustus Parry, who

worked for Captain Homfray, was accused of stealing a diamond brooch

worth around £200 from Mrs Homfray. He appeared before Hove

Magistrates bench and was committed for trial at the Assizes.

Nina Winder Reid (1891-1975) – She was

born in Grand Avenue Mansions. She went on to study at the St John’s

Wood School of Art. She became a founder member of the Marine

Society, and one of the foremost women marine painters in the country

during the 1930s. In 1937 she held her fourth exhibition at the

Arlington Gallery, London. She painted landscapes as well as marine

subjects, and her favourite medium was oils.

Dame Anne Charlotte Seymour – She lived

at Flat 4 in the 1930s. When she died in 1935, she left gross estate

to the value of £61,144. Her legacies included a cabinet of swords

and medals belonging to her late husband, which she left to the

Commanding Officer of the Queen’s Bays (2nd Dragoon

Guards), £1,000 to the Lower Market Street Mission in Hove, and £500

to Hove Hospital.

It seems likely that she was the widow of General

Sir William Henry Seymour of the 2nd Dragoon Guards, who

was the son of Sir William Seymour, Judge of the High Court in

Bombay. General Seymour entered the Army in 1847 and saw service in

the Crimean War. He was a Colonel of his regiment (2nd

Dragoon Guards) from 1894-1920. There was a famous incident on 8

October 1858 during the Indian Mutiny at Sundeela, near Oudh, when he

found himself in mortal danger from a sudden attack by mutineers,

from which he was rescued by Private Charles Anderson and Trumpeter

Thomas Monaghan of thr 2nd Dragoons, both of whom were

awarded a Victoria Cross for their gallant actions.

George C. Tebbit – He and his wife

Elizabeth only lived in Grand Avenue Mansions for a short while in

the 1930s. They were there in 1940 but had left by the end of the

war. Their claim to fame arises from their daughter Mrs Elzabeth

Sparshott who became the close companion of Sir Reginald Fleming

Johnston in the 1930s. Johnston had been tutor to the last Emperor of

China, and interest in him was revived with the 1987 film The Last

Emperor in which Peter O’Toole played the part of Johnston.

Johnston and Elizabeth Sparshott lived together on the Scottish

island of Eilean Righ. They did not enjoy much time together because

they met in around 1935 and he died on 6 March 1938. On his

instructions, she destroyed all his personal papers. In his will, he

left her practically everything, which upset his family. She also

received Eilean Righ, which he wished to be given to the Scottish

National Trust when she had no more need of it; instead the island

was sold. In 2012 the island was on sale for £3 million.

Miscellaneous

In the 1960s actor Gary Brighton lived in Victoria

Court. His first West End role was in Mr Wilberforce MP. He

later appeared in the West End stage production of Annie.

In September 1994 ambulance men were unable to

move a 30-stone woman who needed hospital treatment. The fire brigade

helped out by employing a hydraulic platform to reach the third-floor

flat.

For 35 years until 1999 floats taking part in the

Brighton Lions Carnival parade mustered in Grand Avenue before

setting off along the seafront.

In October 1999 it was noted that 36-year old

Howard Travers held two word records for paragliding. He had been

paragliding for eleven years and also travelled to Australia to

conquer the notorious Bunda Cliffs.

Some Grand Avenue Wills

Eileen Clarissa Mary Walton, spinster, died on 9

March 1979. She left £4 million and most of the money went to

charity. She was the heiress of Covent Garden fruit and vegetable

firm of P. Walton.

Joan Somerville Wallace died on 17 November 1988,

leaving £2,549,364. She bequeathed £100,000 each to the National

Hospital for Nervous Diseases, and the Parkinson’s Disease Society.

Josephine Dalmaine died at the age of 96 leaving

£833,363. In January 1999 it was stated that as a young student at

the Royal College of Music, she met famous musicians such as Holst

and Britten. She taught music first at Roedean and then at Brighton &

Hove High School for Girls. Her bequests were as follows:

Brighton & Hove High School £20,000

Royal College of Music £20,000

Children’s Country Holiday Fund £10,000

Glyndebourne Arts Trust £5,000

Musicians Benevolent Fund £5,000

In 1999 widow Judith Cox of

Victoria Court left

£749,000 in her will to be shared between the Cats Protection

League, the Bleu Cross, and the International League for the

Protection of Horses. Her late husband was London architect and

surveyor David Cox and the couple had moved to Hove some fifteen

years previously.

|

copyright © J.Middleton

The west side of Grand Avenue viewed from

Kingsway |

Sources

Middleton J, Encyclopaedia of Hove and Portslade

Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Hove Council Minute Books

Contemporary newspapers

Copyright © J.Middleton 2018

page layout and additional research by D. Sharp