|

| copyright

© D. Sharp St Patrick’s Church in March 2024 |

The Architect

The land on which the church stands was purchased from Isaac Lyon Goldsmid, and the architect Henry Edward Kendall, junior (1805-1885) designed it in the early English style. His father, H. E. Kendall, senior, was also an architect, and supposedly, a pupil of John Nash. The older Kendall lived to the ripe old age of 99, despite a hunting accident in which the barrel of his gun burst and he lost his left thumb. He was one of the founders of the Royal Institute of Architects, the idea having been suggested to him by his son, and the early meetings took place at his house in Suffolk Street.

Both Kendalls were responsible for designing the Kemp Town slopes, esplanade and tunnel in 1828-1830. Previous to this, Kendall, senior, had designed 24 Belgrave Square, London, for Thomas Read Kemp, the instigator of Kemp Town. It was most probably through this connection that Kemp, junior, received the commission to design St Patrick’s. It is also worth noting that both Kemp and Revd James O’Brien (founder of St Patrick’s) were Freemasons, and at one time the reverend gentleman served as Provincial Grand Chaplain of Sussex.

H. E. Kendall, junior, also designed the Haywards Heath Asylum and chapel, later known as St Francis Hospital. The main building is massive, sporting Italianate towers, and occupying a prime site with fine views towards the South Downs; beautiful surroundings were considered vital for the welfare of the patients. It is pleasant to record that the building was not demolished when care-in-the-community become the latest trend, and instead was turned into flats.

In 1847 Kendall, junior, wrote Designs for Schools and School Houses, from which it is clear he favoured the Gothic style, and schools became something of a speciality for him; he also designed many parsonages.

H. S. Goodhart-Rendel, who designed St Wilfrid’s Church, Elm Grove, Brighton, wrote about the churches of Brighton and Hove too. He obviously did not think much of Kendall, describing him somewhat unkindly as a second-rate man. He did not care for St Patrick’s either, labelling it as stale as yesterday’s crinolines. However, the wheel has turned, and since then Victorian architecture and decoration have come to be more appreciated with St Patrick’s considered one the most interesting churches of that period.

The Church’s Name

The church in Cambridge Road was the fourth church to be built at Hove. The ancient church in Hove was St Andrew’s Old Church, restored in 1836; St Andrew’s Chapel in Waterloo Street was built in 1827, followed by St John the Baptist in 1852.

Originally the Cambridge Road

church was called St James, then it became St Patrick and St James,

and finally it was just St Patrick. No doubt St Patrick was chosen by

the church’s founder, Revd James O’Brien who was of Irish birth

while St Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin had been re-opened in 1865.

|

| copyright

© Royal

Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove St Patrick's original name 'St James' c.1860 image. |

However, the interior of the Hove church was extremely plain, which came as some relief to newspaper reporters who came to inspect the premises. It was noted with some satisfaction that there was a communion table rather than an altar while the windows were filled with an ‘inexpensive species of green-tinted glass.’ The reporter from the Brighton Gazette penned the following:

‘We think we we may safely congratulate the public on the purpose of the edifice being purely that of the promotion of Church of England principles, and not the propagation of any of those particular dogmas so tenaciously held and assiduously promoted which have given rise to much disaffection within as well as without the church.’

The reporter finished on a triumphant note ‘there is no colouring, gilding and emblazoning – there is nothing in the church to to offend the eye of the most fastidious.’

Perhaps the reporter never raised his eyes to the roof because there were some embellishments in the shape of six large, wooden angels with upswept wings. But this was in the days before dormer windows were installed and perhaps not very visible at that time. It is also amusing to note that later on St Patrick’s became famous for its beautifully decorated interior, not to mention its high church practices.

Building and Opening

|

| copyright

© D. Sharp St Patrick’s Church looking south from Cambridge Road in March 2024 |

The foundations of the church were laid in 1857; in October of that year the Bishop of Chichester paid a visit and ‘expressed his pleasure with the building and the progress made.’

The building was designed in the early English style using a bluish stone called Kentish rag, and faced with Bath stone. One part of the design much appreciated by the parishioners was that access to the church was from a cloister, rather than straight from the road as was usually the case with other churches in Brighton and Hove. This feature caused minimum disturbance if someone arrived late while also shielding the congregation from draughts in winter and noise from the street in summer.

A glance at an old engraving shows

that the exterior is much the same as we see it today, except of

course for the tower. In this the church is similar to All Saints in

The Drive, which was also supposed to have a spire. But as so often

the case, the money for this final touch was just not there.

|

| This engraving shows the tower that was never built |

|

| copyright

© D. Sharp St Patrick’s Church's unfinished tower |

It is interesting to note that the Bishop of Chichester refused to hold a confirmation service there in 1859 despite the Revd Walter Kelly of St Andrew’s Old Church specifically asking him to do so because there was more space there than in the old church.

Nevertheless,

the opening service was very splendid, and included the ordinary

service, the litany and communion. It was attended by the Bishop of

Chichester and Archdeacon Otter while the Revd W. Kelly, as vicar of

Hove, occupied the treading desk. The congregation were treated to a

rendering of Handel’s Hallelujah

chorus,

as well as the Te

Deum and

Jubilate.

|

| copyright

© D. Sharp Saint Patrick carving above the north doorway. |

St Patrick’s and Music

The tradition of excellent music started right from the start because Revd O’Brien considered it to be of great importance. When it came to acquiring a new organ he ensured that he obtained specialist advice. Joseph Goss was a member of the congregation, and through him O’Brien was introduced to John Goss, a famous organist and composer who in 1838 became organist at St Paul’s Cathedral.

Goss became chairman of St Patrick’s organ committee, and nominated two other organists, Henry Smart and Edward Hopkins, organist of the Temple Church, London, to join him. Perhaps enlisting such eminent men did not make for plain sailing, and O’Brien felt obliged to take their advice, although some of it was only accepted with reluctance.

For example, O’Brien wanted the organ to be placed in the tower but Goss said that was impossible because the openings were too small for the sound to be heard inside the church. Goss wanted it to be placed in the side chapel (the Lady Chapel) and so the chapel remained thus cluttered up for forty years.

Goss was equally decided about which organ stops would be appropriate, and he put a firm blue pencil through any stops that he considered of a ‘concert room nature’. Thus the vox celeste, vox angelica, and vox maris were removed from the specification. Although approved by experts, it did mean that the organ lacked variety in its softer tones, and twenty-two years later when the instrument was overhauled the opportunity was taken to soften some of the tones.

The prominent organ builder Henry Willis (1821-1901) was the man who built St Patrick’s organ. It turned out to be something of a blue-print because he adopted certain forms of construction that became the prototype of the instrument known as the Brighton model in the factory. Willis finished building the St Patrick’s organ in 1865, and a few years later he was engaged in building the great organ at the Royal Albert Hall. There are two other connections between Willis and Hove; one was that in 1897 he installed the organ with four complete manuals in Hove Town Hall. Then there is the magnificent organ in All Saints, The Drive, which the firm of William Hill & Son always regarded as one of their finest instruments. The first organist to play the latter instrument was W. A. Macduff who had been a pupil of the celebrated Dr Sawyer of St Patrick’s Church.

When the St Patrick’s organ was ready Goss and his two friends came to try it out and pronounced themselves pleased. Goss also suggested that Frederick Bridge should became organist – later on he became organist at Westminster Abbey.

Church Choir

|

| copyright

© Royal

Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove Brighton Herald 7 December 1872 |

|

| copyright

© J. Middleton Two choir boys at St Patrick’s taken in 1927. They are Charles Leonard Caperon (born 10 January 1915) and his brother George William Caperon (born 4 May 1918) |

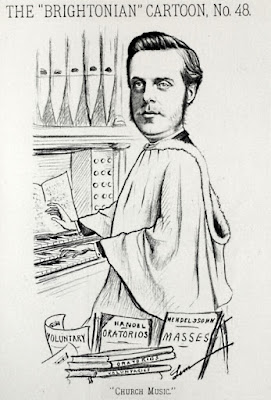

Organists

Robert Taylor

|

| copyright

© Royal

Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove. Robert Taylor |

He was the first organist to be appointed to St Patrick’s Church in 1866, and like his successor, Dr Sawyer, he too was something of a child prodigy, no doubt helped along by both of his parents being keen on music. Robert Taylor was born at Evesham, Worcestershire, and by the age of ten he was the organist at two village churches near his birth-place as well as having been organist at Evesham.

His musical education was no doubt enriched because his family were friends with Sir Edward Elgar’s father, and in 1865 when there was a concert at Evesham, young Taylor played the piano while Elgar, senior, performed at the harmonium.

At the age of twelve Taylor became a chorister at Worcester Cathedral, and when his voice broke, it was no great disaster because he became an apprentice to the cathedral organist. His talents did not stop there either because he became an excellent conductor, not to mention a remarkable organiser. The Brighton Herald described him as being the second most important man in a musical position at Brighton after Mr Kuhe.

Taylor was keen that as many people as possible should be able to benefit from performing or listening to music. He founded the Brighton Musical Union, whose first concert was in 1869 in the hall at West Street, and in 1870 it merged with the long-established Sacred Harmonic Society, with Taylor being their honorary conductor for an astonishing 45 years.

In 1883 Taylor founded the Brighton School of Music in association with with Dr Alfred King and Sydney Harper. It is amusing to note that when it celebrated its Silver Jubilee, Taylor was presented with a ‘silver egg boiler and steamer’ – surely a gift nobody could have guessed.

|

| copyright

© Royal

Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove. Robert Taylor |

In 1870 Taylor became music master and organist at Brighton College, followed by his son Percy Taylor who was still occupying that position in 1915.

Taylor and his family lived mostly at their house in Upper Rock Gardens, but at weekends and holidays, Taylor liked to stay at their cottage at Barcombe where he enjoyed the rural delights of fishing and shooting. In later years, they lived at Keymer. Taylor was fortunate in enjoying a happy marriage and the Brighton Herald described the union as being of ‘singular felicity’. Another son, Sidney Taylor, played the cello in Sir Henry Wood’s Orchestra.

While Taylor was organist at St Patrick’s he wrote a new setting for the hymn O Worship the King and called it, appropriately enough, ‘St Patrick’s’. It proved to be one of the most popular settings for the hymn in Victorian times and during the First World War. But since then it has fallen by the wayside, and the tune more often associated with the hymn is ‘Hanover.’ The hymn is based on Psalm 104, and the words were written by Sir Robert Grant (1785-1838) who was an MP and became Governor of Bombay. It is astonishing to note that there were other Victorian MPs who wrote hymns as well.

Taylor also became the representative of the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal College of Music as an examiner. It is surely entirely appropriate that Taylor chose the test-piece for the Palgrave-Turner Prize at the School of Music – Greig’s The Swan, - and that Taylor breathed his last as the line was sung ‘Aloft thou sprangest as death was o’ertaking.’

Taylor died in December 1915 at

Keymer and after his funeral at St Mary’s Church, he was buried in

Brighton Cemetery on 11 December.

|

| copyright

© Royal

Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove Brighton Herald 1 March 1913 |

Doctor Frank Joseph Sawyer (1857-1908)

|

| copyright

© Royal

Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove. Dr Frank Joseph Sawyer |

Another important person associated with St Patrick’s and its music was Frank Joseph Sawyer. He was born at Brighton on 19 June 1857, the same year in which St Patrick’s began to be built.

Sawyer was appointed organist at St Patrick’s at the early age of twenty but already he had packed a great deal into his young life. For example, he started to compose his own music almost as soon as he began to learn music, and at sixteen he had written an oratorio St John the Baptist. He went abroad for two years to continue his studies, and in 1876 returned to England with a Diploma from Leipzig Conservatorium. This famous institution was founded in 1843, but later changed its name to the Leipzig Conservatory. Sawyer had already obtained a music degree from Oxford, and in 1883 became a Doctor of Music.

Sawyer’s appointment to St Patrick’s in 1877 was an important one for him and the church, and it also showed some imagination on the part of his selectors for choosing such a young man.

Sawyer was an indefatigable worker because besides his church duties, he also taught at the Royal College of Music. He was patient enough to be able to teach young children to sight read music, and was well known for this skill. On a typical day he would be up at 6.30 a.m. correcting proofs before breakfast, then catching an early train to London where he would be teaching all day, either at the College or elsewhere, and finally back again on the late train arriving home at 11.30 p.m. In 1883 he founded the Brighton Choral and Orchestral Society, and in 1904 he founded St Patrick’s Oratorio Society.

|

| copyright

© Royal

Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove. Dr Frank Joseph Sawyer |

Sawyer was perhaps unusual in having an excellent relationship with his church choir. Indeed, it was so harmonious one priest was moved to comment that in 50 years of experience in church affairs ‘I have never known any choir where there is such a total absence among its members of petty jealousies and even open quarrels.’ There was always the stimulus of learning fresh pieces written especially by Sawyer. For example, at the Harvest Festival in 1886 the choir sang a new anthem by Sawyer The Parable of the Harvest, and in April 1892 there was another anthem Remember not O Lord our Offences and a Benedicte, both by Sawyer. It is refreshing to note that despite all his commitments, it was his work at St Patrick’s that was his first and chief love.

It was fitting that his debut at St Patrick’s was on a major festival, Christmas Day 1877, while his last appearance was also on a great feast, Easter Day 1908.

His sudden death came as a great shock to everyone, especially because he always had more than his fair share of energy and enthusiasm. There was an all-night vigil with his coffin resting on the exact spot where he sat at the organ so often during thirty years – it should be noted that the organ had recently been removed to the tower. The next day the church was packed for his funeral.

Soon

afterwards there was a public meeting at Hove Town Hall to discuss

what would be a suitable memorial for him. Eventually, a

stained-glass window was decided upon and placed in the Lady Chapel.

It is not surprising that the subject chosen was St Cecilia because

she is the patroness of music; it was designed by W Bainbridge

Reynolds and executed by the brothers E. and C. O’Neill. The face

of St Cecilia was described as being of ‘refined and youthful

beauty and spirituality’. The inscription runs In

grateful and loving memory of Frank Joseph Sawyer, organist and

choirmaster.

|

| copyright

© J.Middleton The Saint Cecilia window |

Stained Glass Windows

At first St Patrick’s Church had a very plain interior and the only sign of colour to be seen was in the red curtains on either side of the communion table / altar.

Stained glass windows were added

at intervals with the largest of the early ones being the east

(liturgical) one. It was designed by Butterfield and inserted in

1870, the money being raised by the congregation as a testimonial to

Dr O’Brien (founder and first priest) and his wife.

|

| copyright

© J.Middleton The richness of this window is almost overpowering |

A writer in 1893 somehow found in the window the ‘distinctly severe features’ of Butterfield’s style with the chief merit being its good colour. Later critics have been more inclined to use the adjective ‘garish’.

However, it must be said that the subject matter is easily discernable from the nave. The lower half of the window depicts the Nativity complete with Magi, shepherds and assorted animals. Above the Nativity there is Christ enthroned in glory attended by Saints Peter, Paul, John the Baptist, and Patrick. Above this the small central light of the Agnus Dei stand out by reason of its red colour.

Another Butterfield window is a four-light one in the side chapel to the right of the main altar depicting the four evangelists. By 1873 the following windows were all in place; they are ‘Moses striking the rock’, ‘Jacob blessing his sons,’ and ‘Nole Me Tangere’. In addition there are two memorial windows – one donated in memory of Mrs Hopkinson, and the other donated by Miss Gaitskill in memory of her brother.

The window in the Lady Chapel was added in 1895. The subject was also the Nativity but it is a complete contrast to the main window already mentioned. The colours in the Lady Chapel are predominately deep blue and gold, and it seems the inspiration has come directly from Botticelli’s Madonna and Child. The window was designed by W. Bainbridge Reynolds and executed by brothers E. and C. O’Neill. (The same team were also responsible for the St Cecilia window in the Lady Chapel given in memory of the organist and choirmaster Dr Sawyer.)

One cannot help feeling that the writer in the parish magazine was having a slight dig at the main Butterfield window while revealing his preference for the new one when he penned the following: ‘There is no attempt to represent the scene from the historical standpoint, with its accessories of cows (whether with one or two horns), sheep, camels and so on, which in so many instances have produced effects little less than ludicrous, and also have at the same time detracted from the main subject by overcrowding the space at disposal.’

He concludes by saying the new window has one drawback, which was to make ‘all the glass in the church, by contrast, more glaringly defective than ever.’

|

| copyright

© J.Middleton Another brightly-coloured window |

|

| The Architectural Review December 1918 |

Butterfield designed the lectern as well as two stained-glass windows. The lectern is certainly distinctive because although there is the traditional brass eagle with outspread wings, the globe on which the eagle perches is encircled by a band studded with agates, cairngorms, carbuncles, and a green stone known as verd-antique. The supporting column also displays some stones.

Further down the column there is the figure of St Patrick with flowing beard and dressed in his episcopal robes while near his feet writhe six snakes. This alludes to the legend that St Patrick banished snakes from Ireland. The three round towers represent the old Ireland.

In 1873 the lectern was described

thus: it ‘is of large size and great beauty, surpassing anything to

be seen in this part of the country.’

The lectern was donated by a Mr

Tonge.

The Pulpit

|

| copyright

© H. Faulkner The magnificent pulpit |

St Malachi (1094-1148) was archbishop of Armagh, and a famous pioneer of the Gregorian reform in Ireland. Unfortunately his pulpit effigy has had two fingers broken off. St Columkille is better known to us as St Columba; he lived in Ireland for 42 years before travelling to Scotland and founding the monastery at Iona.

On the other side of St Patrick, who looks somewhat dour, is another saint with Iona connections. He is St Aidan who was a monk there, and later became the first bishop and abbot of Lindisfarne.

The last of the sextet is Brian whose name is usually spelt Brian Boru. It is obvious from his stance that he was a warrior – his hands rest on a huge broadsword – and he looks incongruous in such saintly company. He was an Irish hero of the tenth century, starting off as king of Munster, and ending up as chief king of Ireland.

The seated figures are placed underneath ornate canopies and the columns supporting them are of green marble. The spandrils (that is the space between the arch and the top of the pulpit) have a decoration reminiscent of the pulpit theme – the old round towers. In addition there are Celtic crosses and trefoils. These details are apt to be missed because one’s first impression of the pulpit is dominated by the figures between their columns of green marble.

The pulpit was presented by a Mr

Webster.

Revd James O’Brien D. D.

|

| copyright

© P. Burgess Pen and ink sketch by Patricia Burgess |

James O’Brien was born on 25 July 1810 in Ireland. He was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, and he became a graduate of Hereford College, Oxford, where he gained a B. A. and M. A. becoming a Doctor of Divinity in 1863. It seems he also made some study of law before deciding on taking holy orders. He was aged 31 when he was made a deacon, and he was priested in 1842. On 13 August 1844 he married Octavia Hopkinson in the parish church of Upper Chelsea, and on the marriage certificate both fathers were described as ‘esquire’ under rank or profession.

It is apparent that O’Brien was one of those clergyman whose great knowledge is not easily distilled into a sermon, and even in the fulsome obituary the writer was obliged to concede the ‘deceased clergyman was not what was known as a great preacher.’ His sermons tended to be marked by logical arguments that might have harked back to his legal training. Towards the end of his life he gave up preaching altogether, leaving the task to his curate. Indeed, his junior curate once remarked that he had never heard him preach in two years. There was an amusing tradition that O’Brien had honed his utterances to just two sermons, both of them suitable for Christmas Day, which he used alternately.

What

O’Brien lacked as regards the spoken word, he more than made up for

in the sung word because he had a ‘great taste for church music.’

It was said that his quiet influence led many Brighton churches to

adopt ‘intelligent musical services.’ During his incumbency St

Patrick’s built up such a reputation for its choral services that

at the time of his death the church was ‘famous for its musical

excellence.’ The Revd W. J. Harvey could say without doubt ‘we

were the

musical church in the neighbourhood.’

O’Brien was a Freemason, and he also took an interest in local affairs, serving as one of the Hove Commissioners. He died on 8 January 1884 having suffered from a chronic bronchial condition for some time.

It was only fitting that there should be some special music at his funeral. This consisted of Handel’s Funeral Anthem, and other music by Croft and Purcell, the same music having been performed at the funerals of Nelson and Wellington. The following Sunday at St Patrick’s the anthem Brother, thou art gone before us by J. Goss was sung.

O’Brien was buried south-east of St Andrew’s Old Church, Hove. Fortunately, the grave is situated in the south part of the churchyard, and so escaped destruction when much of the north churchyard was flattened. The memorial takes the form of a grey granite cross inscribed at the base James O’Brien D. D. Founder and first incumbent of St Patrick’s Hove.

The Court Case

The O’Briens did not have any children, and Octavia died on 26 May 1884, just over four months after her husband’s death. She was highly thought of in the community, and one curate described her as a saint indeed.

Their wills provide a complete contrast to each other. His will dated 2 July 1879 was very simple and short. He left everything to his ‘fond and devoted wife.’ It was witnessed by two servants – Charlotte Packham, parlourmaid, and Harriot Hall, housemaid

By contrast Octavia’s will ran to five pages of detailed bequests, and was witnessed by William Sayer, a Westminster solicitor, and Dudley Haggar, secretary to Sir Philip Rose. She did not forget the maids either, the parlourmaid was left £30 per annum and the housemaid received £20 per annum.

The O’Briens had plenty of nephews and nieces. Octavia’s brother, Charles Hopkinson, had no less than five daughters and three sons while her sister, Harriet Daniel-Tyssen had two sons and one daughter. Two of the nephews were important in the history of St Patrick’s, namely Revd Edward Ridley Daniel-Tyssen, and Revd George Edward O’Brien. (There was another clergyman in the extended family too, Revd Edward Robert Cruickshank, who was married to Amelia, Octavia’s niece, but they seem to have steered well clear of the ensuing row).

|

| copyright

© J.Middleton Detail of an ornate column |

Revd George O’Brien was left £6,000, Octavia’s bureau, and number 35 Cambridge Road. Revd, R. Daniel-Tyssen received £200 for his role as one of the executors of the will, a share in the family silver plate, and number 16 Brunswick Place, Hove, formerly called the Parsonage House, together wit all its contents. Octavia pointed out in her will that he received less than his brother and sister because he was ‘the vicar designate of St Patrick’s Church by the will of my late husband,’ and that anyhow she considered her bequest to be the equivalent of £2,600 in cash. It was not this clergyman that was dissatisfied with the will because it was George O’Brien who was angry and decided to lay claim to being the vicar of St Patrick’s.

This is where matters become complicated. Dr O’Brien’s will made no mention of St Patrick’s, and Octavia made only the oblique reference to it quoted above, and so it was thought there was some secret trust between them as to what should happen to the church. Such secret trusts were not so uncommon as might be thought. Such a trust would mean that the wishes of one party would be carried out by the other party without the necessity of spelling it out in black and white in the will.

Dr O’Brien apparently also wanted St Patrick’s to achieve the status of a parish church. Towards this end, Octavia made enquiries about donating the church to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. But for this to be done legally, the deed had to be conveyed to the Commissioners at least twelve months before the donor’s death. Octavia felt that she would not live long enough to fulfil this requirement, and indeed her will was made just over a month before her death. Therefore in the same month in which she died, she made over St Patrick’s and its site to Revd Daniel-Tyssen.

This is where Revd George O’Brien stepped in, claiming he was heir-at-law of Dr O’Brien, that the secret trust was illegal, and that he was the rightful owner of the church. It was the up to Queen’s Councillors to argue the matter in the Chancery Division of the High Court before Vice-Chancellor Bacon.

The defence case was that even if the trust were affected by the Statute of Mortmain, which they would not admit to, it was valid under a subsequent Act 43 George III. There was a fine distinction here because this act covered a gift of land for the purpose of building a church thereon, whereas the plaintiff asserted the act did not cover a piece of land with a church already on it. The Vice- Chancellor interpreted the Act as meaning that a person might provide a site for a church or present the fabric if it already existed. George O’Brien lost his case.

The papers relating to this action were one of a number of Chancery classes of records that have been destroyed. Therefore, information has had to be gleaned from various contemporary newspaper reports. Just two documents have survived.

An Affidavit of George Robert Hubbard in support of an application to examine the Bishop of Chichester and Revd James Vaughan as material witnesses.

The examination of the Bishop of Chichester himself.

The name of G. R. Hubbard is another wheel within a wheel. He was the solicitor for the plaintiff O’Brien. He was also a relative, most probably the brother-in-law of his client. In Octavia’s will she left her piano and £6,000 to be invested for her niece Helen Elizabeth Hubbard, and on her death the income was to go to G. R. Hubbard.

The two clergymen cited in the affidavit were both elderly men. Revd James Vaughan was around 80 years old He first came to Brighton in 1836 when he served as curate at St Nicolas Church, and from 1838 to 1886 he was to be found at Christ Church, Montpelier Road. However, in the Directories he was listed as being curate of St James Church in 1861. In contrast to Dr O’Brien he was a very able preacher, and several volumes of his sermons were published, not always in accordance with his wishes it would seem. He was heard to grumble on more than one occasion that reporters ‘make me to say not only what I did not say, but what I should not think of saying.’

Richard Durnford, Bishop of Chichester, was 82 years of age, and had not experienced a tranquil episcopate. There was the continual controversy of Catholic practices to navigate besides dealing with Father Wagner, and now the controversy about St Patrick’s Church. Nevertheless, he managed to live to a ripe old age, and died aged 93 in 1895.

The examination of the bishop took place on 21 July 1884 when he was obliged to recall details of any conversations or letters that had passed between himself and Mrs O’Brien. He stated ‘I looked upon her as holding it (St Patrick’s) under her husband’s will, and as having the power of disposing of it as she pleased.’ He was aware of negotiations going on between her and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners but did not interfere on the grounds of delicacy. She had already told him she intended the patronage of the living to be vested in the Bishop of Chichester, providing her nephew Daniel-Tyssen became the next incumbent.

What of the instigator of the case – Revd George O’Brien? Like his uncle and cousin, he was an Oxford graduate. At the time of the court case in 1884 he was curate of Buxton. He had only been in holy orders for twelve years but had already notched up eight different curacies, including a short spell at St Patrick’s 1878-1879.

The question remains as to why he was so set on having St Patrick’s, despite the generosity of Octavia’s will? St Patrick’s was a fashionable church, and the pew rents brought in £1,100 a year, with a peak of of £1,217 in 1868. Perhaps he took his defeat philosophically because he penned Regeneration into Baptism published in 1886 by which time he had removed himself to a parish in Manchester.

The Reredos

When Revd James O’Brien died in 1884, having served St Patrick’s Church for 25 years, it was felt that this should be commemorated, and a committee was formed to to consider what sort of memorial would be appropriate. After some deliberation, the idea of a reredos was put forward, and it was known that this would have been in accordance with O’Brien’s views.

It did not take long before £520 had been paid in, or was promised to the fund. Then came the court case, and planning came to a halt. The matter was described discreetly in the church magazine as ‘unfortunate circumstances’.

Holy Trinity, Ship Street: He installed a new facade of Gothic design in 1885-87.

St Nicolas Church, Brighton: He designed the foliage murals in 1892.

St Peter’s Church: He enlarged the church. You can see the dividing line between the two because Somers Clarke’s larger chancel was built of darker stone than the original Portland stone.

Somers Clarke had local connections, being the son of Somers Clarke, senior (1802-1892) who served as Vestry Clerk of St Nicolas for over 60 years, besides being a partner in a legal firm.

Somers Clarke, junior, lost no time in designing the reredos for St Patrick’s, and just four months after being asked, his design had been seen and received committee approval by July 1886. Unusually, the material chosen for the reredos was red sandstone from quarries near Aberdeen. It is generally assumed that Victorians were obsessed with white marble, but in this case it was felt the sandstone would provide a warmer tone to the sanctuary than cold marble.

The centre of the five panels

depicted the crucifixion and this panel projected slightly beyond the

others. Originally, the cross was to be accompanied by figures of St

Mary and St John. However, that plan must have been modified because

today there is an angel kneeling on either side. The other four

panels were devoted to the evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

Another alteration was the gilding. In 1886 the only parts to be

gilded were the ornamental canopies over the figures, but at some

stage it must have been decided to add more emphasis to the body of

Christ by gilding the figure, not to mention the wings of the

attendant angels.

|

| copyright © H. Faulkner |

The work of installing the reredos started on 21 April 1887 and it was expected, somewhat optimistically as it turned out, to be completed within one month. While the work was on-going, daily services had to be to discontinued The opportunity was taken to carry out a much needed improvement. This was to insert three dormer windows in the western roof of the chancel that would provide more daylight, and enable the reredos to be seen more easily. It was also hoped that the extra light would avoid having to use the gas lights during the day. The estimated cost of the windows was from £150 to £170.

Underwood & Sons asked for an extension of time in finishing the reredos. It was disappointing because it had been hoped to have a grand unveiling on Ascension Day. But only one man was responsible for doing the carving, and if an additional carver were to be employed, it would spoil the integrity of the piece.

The magazine for July 1887 carried the welcome news that the reredos was now complete. The towers flanking the central portion carried the following Inscription: To the glory of God, and in affectionate memory of James O’Brien D. D. founder and first incumbent of this Church, born July 25th 1810 died January 8th 1884. This reredos was erected by the congregation of this church and a few personal friends.

The Frescoes

Octavia O’Brien died not long after her husband’s death. It was remarked that she had led a ‘singularly unselfish and kind life’ and it was always intended that she should have a memorial too. But a delay was inevitable because the reredos had to be paid for and finished first of all.

It was decided that Octavia’s memorial should take the form of frescoes on the chancel walls. At first it was going to be a modest undertaking on perhaps one wall, but then it was decided to carry on painting the chancel so long as the money permitted. Fortunately for visual unity, this hope was achieved.

Clayton

& Bell designed the frescoes and work started in 1890. The design

is thought to stem from a verse in the Te

Deum

that declares ‘the

Holy Church throughout all the world does acknowledge thee.’ The

central part is the figure of Christ in glory but unfortunately

because it is painted high up in the apex of the roof, it is the

least visible part of the frescoes, being always in shadow.

|

| copyright

© H. Faulkner Note the wooden angels above the frescos |

In consideration of the new frescoes, it was decided that electric lights should be installed in the chancel at a cost of £30 to prevent the paintings from ‘being injured by the smoke of the gas.’

However, the rest of the church had to make do with gaslights for the time being. It was not until 1894 that electricity was installed in the rest of the building at the ‘heavy’ cost of £250. It was hoped that consequently the church would be cooler on summer evenings since the air would ‘not be so vitiated.’

The Mosaics

|

| copyright

© J.Middleton The Virgin Mary singing the Magnificat |

|

| copyright

© J.Middleton King David and his harp |

These two mosaics both have alabaster frames. A similar alabaster frame around a tablet is to be found in the south chancel aisle dedicated to Patience Walrond. There are two small mosaics on either side. Powell of Greyfriars was also responsible for this work.

The Font

For fifty years the square font at

St Patrick’s Church was almost severe in its plainness. Perhaps

some people thought that this stolid font was somewhat out of keeping

with all the colour and ornament flourishing in the rest of the

building.

|

| copyright © H. Faulkner |

The enterprising vicar carefully saved spare pieces of marble from the construction, and had them made into paperweights. The white marble ones were cheaper at five shillings, but for a green marble paperweight you had to fork out 7/6d.

|

| copyright

© Royal

Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove St Patrick's Church in 1903 |

The Stations of the Cross

The idea of installing the Stations of the Cross grew from the wish for a fitting memorial to Revd S. H. Rutherford, vicar 1923-1945. However, it soon became apparent that the money in hand would only be enough for six paintings, and so an appeal was made to the congregation to donate enough money for eight paintings -either as memorials or thanks-offerings.

|

| copyright

© J.Middleton The head of Minerva by Charles Knight |

|

| copyright

© D. Sharp The Ginnett Memorial in the Woodvale Cemetery, Brighton. |

The Stations of the Cross were dedicated on 21 December 1947 by the Bishop of Lewes, Canon Geoffrey Warde, one-time vicar of Brighton. The paintings were much admired, and it must have been gratifying to receive an enthusiastic letter from H. Hamilton Maugham, who was an authority on church architecture and furnishings. The letter was duly printed in the church magazine stating that the paintings ‘have not only beautiful colouring, but many striking touches of originality in treatment.’

Revd Ridley Daniel-Tyssen

It is interesting to note that when this priest was inducted to St Patrick’s in April 1885, it was also felt proper to consecrate the church, which had never taken place because Baron Goldsmid had been too ill to sign the necessary documents. Some people wondered whether or not it was worth the bother, seeing as the church had been functioning satisfactorily for many years. The bishop therefore in his sermon pointed out the legal implications. He said that ‘without consecration it (St Patrick’s) could not be the centre of a parish, as he was sure they all desired so noble a building might be. It had no ministers recognised by law, and could have no churchwardens appointed to legally represent the lay people. Therefore the consecration of this great and noble building, so long desired, was not an idle ceremony.’

A letter from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners dated 21 August 1885 gave the news that the Queen in Council has assigned ‘a district chapelry’ to St Patrick’s Church. The letter was addressed to Revd Thomas Peachey, who was vicar of All Saints, Hove 1879-1909. The news was also printed in the London Gazette.

One of the first things Daniel-Tyssen did was to inaugurate the church magazine in January 1886. He was not to know what a mine of information these magazines would be to future historians.

During his incumbency St Patrick’s was affiliated to St John’s Church, Carlton Hill, Brighton. The latter was a very poor parish, and the vicar, Revd E. Riley, who himself had but a small income and no vicarage, was asked to come and explain to the people of St Patrick’s how they might help. Thus for some thirteen years financial help was given to St John’s.

An unusual charity was the Flower Girl Mission in which private donations from St Patrick’s enabled girls from St John’s to receive lessons in reading, writing and arithmetic on two evenings a week; these unfortunate young girls scraped a precarious living by selling flowers to passers-by.

In 1900 the congregation’s energies were re-directed to Hove where the new church of St Thomas the Apostle was being built. This was to be a daughter church to St Patrick’s, and remained so until 1924. It was Daniel-Tyssen who realized that with all the new buildings going up in Hove, this part of his parish required its own church. Mr d’Avigdor Goldsmid donated the site, which was considered ‘exceedingly eligible’ both because it was situated on a main thoroughfare, and because the roadway was on a higher level than the ground. This meant that vestries and other rooms could be built underneath the church with one roof covering the lot. It might be more expensive initially but would be a saving in the long run. Clayton & Black were the architects.

The people of St Patrick’s took a keen interest in the progress of the new building. In November 1911 a Grand Bazaar in aid of the building fund was held at Hove Town Hall. It realized the sum of £490, and the bazaar was described as having been a phenomenal success.

Meanwhile, in 1904 Daniel-Tyssen had been obliged to resign because of his wife’s ill-health, and he took her to Italy. Whatever her ailment she made a remarkable recovery and lived on until 1930. Daniel-Tyssen returned to Hove and did more good works. He died aged 76 on 27 March 1917. There is a memorial tablet to him placed high on the chancel wall on the right side of the altar.

Revd Walter Marshall

He was vicar of St Patrick’s from 1904 to 1919. He had been a minor canon at St George’s chapel, Windsor from 1888-1900, and before coming to Hove he was rector of Ewhurst, Sussex.

At St Patrick’s he instituted a

new style of parish magazine, and there were no longer any

advertisements. He was also keen on restoring the Lady Chapel to its

original use, and to hold daily services in the chapel. But first

there was the impediment of the organ being situated there.

Fortunately, a more recent assessment concluded that it was perfectly

feasible for the organ to be moved to the tower by opening out the

two existing arches in the second stage of the tower. It was stated

that £1,500 was needed to rebuild and renovate the organ.

|

| copyright ©

St Thomas Church Jubilee Booklet 1965 St Thomas the Apostle |

|

| Musical Times 1 May 1915 The Barless Psalter (1915) by the Revd Walter Marshall and St Patrick's organist, Seymour Pile. |

After leaving St Patrick’s in 1919 he became vicar of Christchurch, Hampshire, where he died on 6 March 1921. He was described by his successor as a ‘man of arresting, attractive personality as well as refined and cultivated tastes, who will long be remembered as a magnificent figure in the English Church Pageant.’

Revd Robert Raikes Needham

It seems likely that the two

reverend gentlemen did a parish exchange. It is a fact that Marshall

went to Christchurch, Hampshire, which is precisely where Needham had

been vicar 1916-1919.

Although Revd Needham carried a famous name – that is Robert Raikes – it seems that it had absolutely nothing to do with his immediate family. In other words, there was no relationship. It must mean that his parents were admirers of this man.

When Needham came to Hove, he found ‘a stately church with a fine musical tradition.’ The services were also simple and straightforward but, with the backing of the congregation, he soon introduced the ‘accessories of Catholic worship.’ This included coloured vestments, copes, six candles on the altar, and three years after his induction, incense.

Another first for St Patrick’s, and indeed for the whole diocese, was the introduction of Gift Day. The vicar was in the church to receive offerings and for every gift at the altar rail, the giver received a blessing. It was certainly different from the usual impersonal money gathering. It proved to be so popular that by the end of the day there had been 476 contributors and the astonishing total received was £930-13-2d. As a result the reredos was re-gilded, while the chapel near the tower received a new baldachino and altar as a memorial to those killed in the First World War.

The vicar was also well-supported by his parishioners. In those days, but not now, it was the tradition that the Easter offerings were given to the vicar. Needham was far too discreet to publish the result of the five Easter offerings he received at St Patrick’s, but no doubt the money was useful in supporting his son at Oxford University.

In 1923 Needham’s health was causing anxiety, and he decided to take on a smaller church and parish at St Michael’s Church, Lewes. Whatever was the matter with his health it could not have been serious because in 1958 he celebrated his 100th birthday.

Revd Stanley Howard Rutherford

He was the vicar for 22 years. He built on the foundations laid by his predecessor, and enhanced the Catholic tradition. During his time some £13,000 was spent on St Patrick’s – mostly on restoration work, and the church soon became ‘one of the most ornate in the district.’

Rutherford also managed to succeed where others had failed – namely the abolition of old-fashioned pew rents. The situation was not as bad as in other proprietary chapels because some pews had been set aside especially for the less well-off who only paid a nominal sum. The Brighton Herald of 1858 thought this was very democratic because a poor man could have his own seat, just the same as a rich man. By 1866 it was stated that ‘for the evening service no pews are let or appropriated, so that rich and poor may sit together.’ During O’Brien’s time, the verger Dean had perfected the art of ensuring people paid up on time; while escorting them to their seats he would say ‘in a perfectly audible voice that their pew rent was overdue.’

When the church of St Thomas the Apostle became independent of its mother church, it was also given part of St Patrick’s parish. Therefore, Rutherford negotiated to acquire the conventional district of St Andrew’s, Waterloo Street, when the incumbent left. This kept the population of the parish up to over 4,000 people, the qualifying number to apply for an endowment.

Rutherford died suddenly in 1945

after a serious operation in the London Clinic. He left a widow,

three sons and one daughter. There was an impressive funeral service

at St Patrick’s, but sadly none of his sons could attend because

there was a war on, and they were all in the Services. Six Stations

of the Cross were commissioned in Rutherford’s memory.

|

| copyright

© Royal

Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove. Brighton Herald 7 July 1917

Coincidently just over 10 years after this wedding, one of the

seven-ton guns from the Königsberg was

on display at Hove’s Coastguard Station / RNVR Depot near the King Alfred site from 1928 until the outbreak of the Second World

War.

|

Other Vicars

Revd William Percy Wylie came to St Patrick’s in 1945 but only stayed a short time. He had previously served at Uckfield and at St Richard’s Church, Haywards Heath.

Revd Robert William Nicholls arrived at St Patrick’s in 1949, having spent the previous ten years at Horsham. The local Press liked to refer to him as ‘Hove’s canoeing vicar’ because that was his long-standing hobby; he had canoed down most of the rivers in western Europe in this way. For instance, in 1956 he spent his holiday ‘paddling down a river in the north of Spain.’

In October 1956 Nicholls was aboard a much larger vessel – the British liner Mauritania on his way to the United States; he had exchanged parishes for one year with an American priest, Revd Donald C. Schneider of Grace Church, Carthage, New York State.

The Schneiders, both of them former newspaper reporters, arrived at Hove in November of that year. They got on very well with the verger Sydney Stagg, and after returning home, urged him to come to America for a holiday. He did so in 1961, and again in 1967, leaving his daughter, Mrs J. Griffiths to hold the fort as verger. Stagg was on his second visit when he died suddenly; he had been verger at St Patrick’s for 37 years.

Revd Maurice Valentine Mandeville became the next vicar in 1958 when St Patrick’s celebrated its centenary. At his induction he was described by the Bishop of Lewes as ‘an old and faithful servant of the diocese.’ He had been a curate at Eastbourne in the 1930s, and later he became vice-principal of Chichester Theological College. He was assistant master at Ardingly College 1943-46, and at one time had been chaplain to the British Embassy, Helsinki. His travels were not over yet, and after only fve and a half years at St Patrick’s, he left to work in Accra, Ghana.

In 1964 the new vicar was Revd Cecil Eldred Curwen, a Kelham priest like Mandeville. Curwen was in London during the blitz, and he used to take his dog Chum (a Labrador cross cocker spaniel) to services with him because he did not want to leave him alone during raids. The church was All Saints, Surrey Square, Walworth, and it was hit no less than three times, being destroyed altogether by a bomb in April 1941. But Chum died of old age after the war.

|

| copyright

© J.Middleton An old postcard view of St Patrick's Church |

Meanwhile, what about St Patrick’s? The prognosis looked bad from the south because the church appeared to be rearing up from a chasm that extended to Western Road. Services could not be held inside the church until it was properly inspected. A garden wall in Brunswick Place had buckled, and flower beds had subsided some three feet. So it was a great relief when St Patrick’s was declared to be structurally sound.

Pearson left the following year, and Revd P. R. F. Sanderson became the vicar for five years. St Patrick’s was familiar to him because he used to attend services there as a boy. However, it was recognised that some people living in the Brunswick area suffered from social deprivation, and it would need more than just a vicar to try and build more social awareness. For this reason and others, two young priests were assigned to the church.

On 26 July 1979 Revd Peter Clark was inducted to St Patrick’s. It is confusing because he had recently spent four years as rector of another St Patrick’s Church, but this one was in Grenada, in the Diocese of the Windward Islands.

It is sad to record that after such a brilliant history, people attending services at St Patrick dwindled to a trickle. What to do with a large, almost empty church? Revd Alan Sharpe, who arrived in 1983 hit upon the idea of establishing a Night Shelter for homeless people at the back of the church. This has been an on-going service ever since but in February 2024 Brighton and Hove City Council announced they were withdrawing their support. It was claimed that closing St Patrick’s high support rough sleepers’ hostel would save £364,000. However, it was also reported that the building could not be retained any longer, and therefore the shelter would be closed at the end of March 2024

There

was another blow when the Heritage

at Risk Register published

by Historic England named St Patrick’s Church as being in danger of

being lost for ever.

See Also St Patrick's Night Shelter

Illustrations

The black and white photographs were taken in 1981

The colour photographs were taken on 24 June 2002

The pen and ink sketch of the Revd James O’Brien D. D. was by Patricia Burgess, 1981Sources

Argus (2/2/24 / 16/3/24)

Brighton Gazette

Brighton Herald (11/12/1915)

Brighton and Hove Herald

Church Times

Evening Argus

Sussex Daily News

***

Bradley, I. The Daily Telegraph Book of Hymns (2005)

Encyclopaedia of Hove and Portslade

Porter,

H. C. The History of Hove

(1897)

Royal

Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Middleton, J. History of Hove (1979)

Needham, R. R. Just for Remembrance

St Patrick’s Church Magazines (from 1897)

***

The Keep

PAR 387/7/1058

PAR 387/10/19

PAR 387/10/20

PAR 387/10/21/2

PAR 387/10/21/22

***

Dr O’Brien’s will dated 2 July 1879

Mrs O’Brien’s will dated 5 April 1884

***

Public Record Office

Affidavit J4/2376/525

Pleadings J54/bundle 389

Information about H. E. Kendall from the British Architectural Library, and Royal Institute of British Architects

Copyright © J.Middleton 2024

Page Design and Additional Research by D. Sharp